Instruction versus exploration in science learning

I came across this article on the APA website.

This question may be answered by David Klahr, PhD, a psychology professor at Carnegie Mellon University, and Milena Nigam, a research associate at the University of Pittsburgh's Center for Biomedical Informatics. They have new evidence that "direct instruction"--explicit teaching about how to design unconfounded experiments--most effectively helps elementary school students transfer their mastery of this important aspect of the scientific method from one experiment to another.

...

Klahr saw three main reasons to challenge discovery learning. First, most of what students, teachers and scientists know about science was taught, not discovered, he says. Second, teacher-centered methods (in which teachers actively teach, as opposed to observe or facilitate) for direct instruction have been very effective for procedures that are typically harder for students to discover on their own, such as algebra and computer programming. Third, he adds, only vague theory backed the predicted superiority of discovery methods--and what there is clashes with data on learning and memory. For example, discovery learning can include mixed or missing feedback, encoding errors, causal misattributions and more, which could actually cause frustration and set a learner back, says Klahr.

Yet discovery learning has persisted, he says, partly because of a lingering notion that direct instruction would not only be ineffective in the short run, but also damaging in the long run. Piaget thought interfering with discovery blocked complete understanding. More recent cognitive research, says Klahr, shows that "this is just plain wrong."

Study after study disproves the current "inquiry" approach to education, yet if you mention direct instruction among a significant portion educators you might as well just call yourself a martian.

(cross posted at KTM part deux)

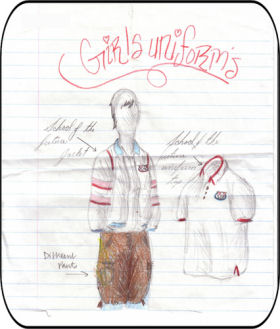

I do have to admit, its pretty fricking cool. Of course what's cool today is geeky tomorrow. Maybe we should of got these kids to design our new hideous Airman Battle Uniform.

I do have to admit, its pretty fricking cool. Of course what's cool today is geeky tomorrow. Maybe we should of got these kids to design our new hideous Airman Battle Uniform.